By mid-July, there had been about 50 days of protests. According to LMPD, 435 protesters had been arrested. On July 24, protesters marched into the NuLu area of Louisville and blocked the 600 block of East Market Street with metal barricades and set up long metal tables for an impromptu block party to highlight demands for NuLu business owners, including hiring a more proportionate number of black workers. Police cleared the street and arrested 76 protesters who refused to leave. (Wikipedia)

Tonight’s midnight watch starts with Jordan. He is from St. Louis and looks to be about eighteen years old. I asked him how he got to Louisville, and he told the all-too-familiar story of a bus ticket handed to him by the Police with the warning to go where the ticket says and … don’t come back. He is a soft spoken kid wearing sandals and a hoodie with shorts. He politely said,” All I want is coffee.”

As I handed over some fresh, scalding hot coffee, he asked for a cigarette and asked if I had a gun for protection. I told him I don’t own a weapon, and he suggested that God must protect me. I told him no, “God just deals the cards; we defend ourselves and discard bad decisions.” He then lifts up his shirt, and with a wink of an eye, reveals a long-bladed kitchen knife and tells me he’s getting good meals from the activists in Breonna Taylor Park. As he walked away, careful not to spill his coffee, he warned that the black panthers were coming and added loudly … that if somebody shot him, they better shoot him dead cause he would fuck them up if they didn’t.

It’s thick tonight. I am tired. This is my first shift back from off days, and the wharf riverside is ominously quiet. Interstate traffic rolls by in surges of pulsating silence like the roar of ocean waves. There is a pungent, dead fish smell hanging in the air. United Parcel Service jets fly overhead every thirty seconds blaring out the sound of crickets that come and go as the city’s noises roar and fade. I am tired, didn’t sleep a wink this afternoon, though I tried to force myself to nap. A swing-shift-watch-duty already puts a person into a dreamy, cloud-like haze. Tonight is dark. I feel on’ry and mean.

An old poet-friend advised back in the day to write it out when faced with big life problems. Tonight, I plan to write this night into a morning sunrise. Another jet just flew over. A ripe, humid breeze is blowing in from the city across the boat. The lines are tight, and all is well at 00:43.

Many were arrested tonight —the city is rattled and being pulled into its current state of discord, by a generation of brave, young truth seekers who are willing to put it all on the line. Monuments to lies are collapsing, and whitewashed narratives are coming down with them.

This group of young protestors are like a wild river pushing against a dam constructed of whitewashed history. When it breaks, an abundance of information and resolve will churn the disturbed waters into a thick silt of muck. After the activism recedes, time will tell if narratives change or if boundaries were resettled. History can only be made. What is dredged up from the past, must be set aside, and time will do what time does to things laying out in the open.

There is rain on the radar off to the west. It would be great if we got a cooling downpour mid-shift to cool things down. I am sitting in the Broaddus and have just eaten supper. Split pea soup from a can, ramen noodles from the health food store, a little cheese, crackers and coffee. Thick ass black as fuck nasty old coffee in a styrofoam cup. The Broaddus is an engine-less crew room that floats on a steel deck that is named after a Louisville Mayor who was long forgotten in a past that just fell by the way. And I am a stranger too, ya know, these long hours up in my head are like a road trip mentally too far gone to return.

The picnic tables I’m sitting at are painted a thick green. Coats of oil paint so dense, that the table seems wet from a fresh painting because of the heat and humidity of this day. This place is jam-packed with extra paddlewheel wood, parts, memories and junk. The meditative hum of two fans blowing warm air mixes with the occasional crackle of the marine radio. Tug operators talk to the McAlpine locks as they push down and upriver. For a creative writer or an overly romantic folk musician, this job is a dream. I can see the Belle of Louisville tied securely to this office just outside a big door. I am floating on the Ohio River as I write this.

Back out at the wall on the Wharf to have a smoke. Anytime I walk off the boat, something strange, weird, profound or possibly dangerous could happen. Most watch-people do not hang out on the Wharf. I do. I can see all three boats, and I enjoy raw life. I know many of the homeless street folks who seek refuge here at the river’s edge and feel at ease with them. Jordan is sleeping on the wharf benches and can’t understand why I don’t shoo him off. I’ve been told to stop giving the wharf rats coffee, but for the price of a measly cup of coffee, I am buying one less person to worry about that might damage one of our boats.

Many wharf folks, especially the late-night fishermen, tell me who is out here, and partly, that is all part of the midnight shift change report. In our first short conversation, Jordan told me to watch out for this new guy hanging around the trolley stop. I already knew about him and told Jordan that I treat people equally regardless of their situation. Out here at this wall, I can see all the way upriver and all the way down to the dark places under the expressway. The wall is my office table, and I am sure Jordan will wake up and come over soon to tell me more about what is in store for tonight’s watch.

He had a shoe box under his arm and placed it on the wall. I could see stuffed animals sticking out of the broken top and was curious to know what else was in it. He proudly pulled out two bras, a hat, and some knick-knacks he had gathered for a friend who, he says, “needs anything she can get.” I am pretty sure Jordan is a sex worker. He told me he made a few dollars “down there,” pointing down to the dark part of the Wharf. “I took my friend out to White Castle with the money, and then we smoked some spice and fell asleep together,” he mentions matter-of-factly as he packed up his box and walked off into the unknown of the rest of his night.

I’ll most likely see him several times tonight. One of his co-workers told me how this all works down here. People come to the parking lots starting at the Big Lawn to find favors. After a short ride, the customers let their person out somewhere, most likely down here, and the process starts again. You have to watch the dudes on the bikes —because they are the ones running the game. I don’t talk to them, and they don’t speak to me. They collect their cut and sell whatever the new street drug is. Right now, it is spice. Even the people who fly the cardboard signs on the offramp at River Road and 3rd Street have a pimp. The Police know, and the city doesn’t seem to care, but you would never know if you didn’t. I know, and for some reason, these folks see me like the Padre’ from M.A.S.H. I must get off the Wharf and hide; being nice isn’t easy.

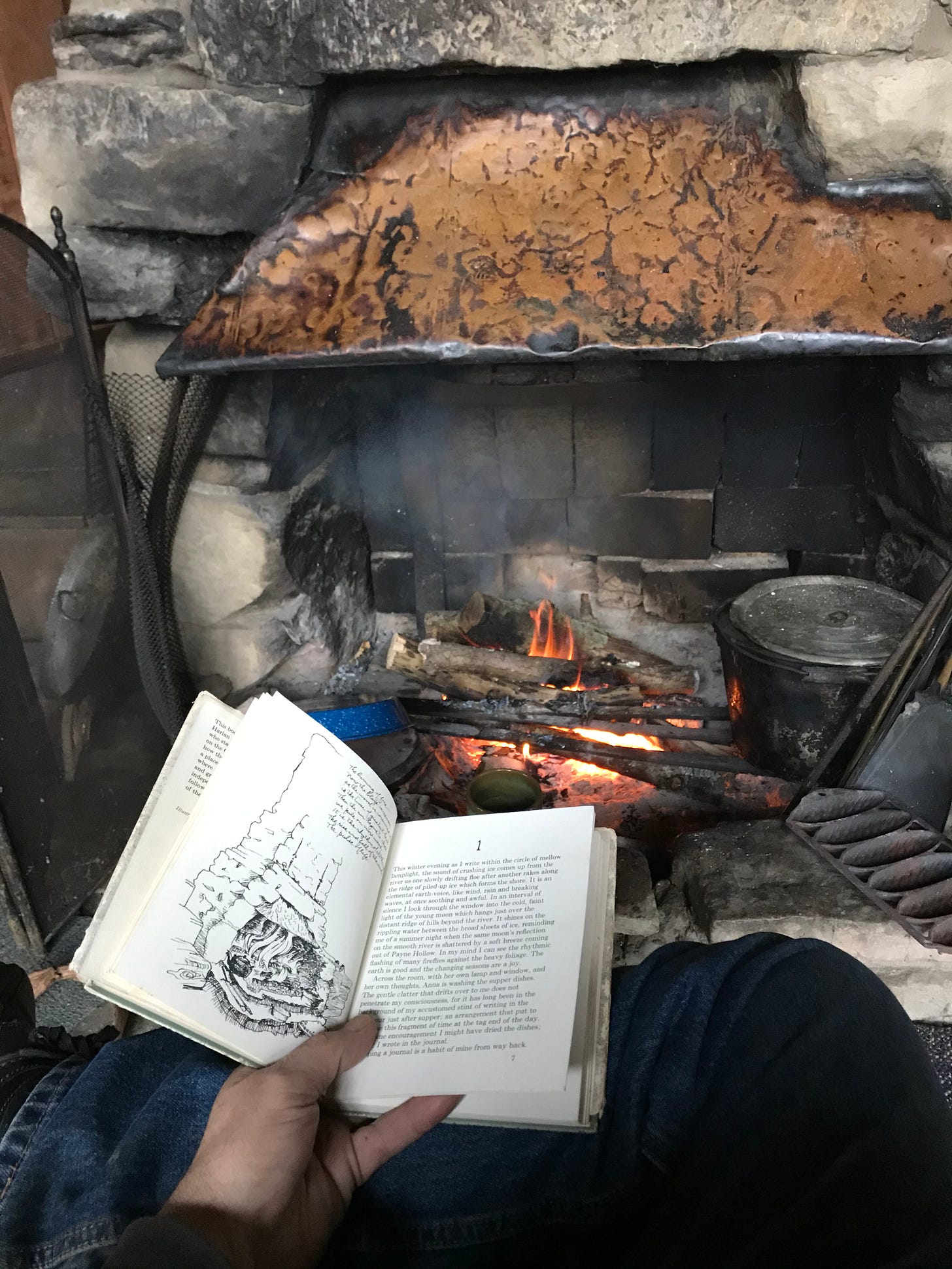

I plan to go up to the pilot house and read. I’m reading Harlan Hubbard’s book “Shanty Boat” and have some questions. I’ll probably call my friend Paul; he loves that we talk from the pilot house. Paul is the caretaker who inherited Payne Hollow. Harlan loved steamboats, and Paul likes to talk about Harlan. Paul lives in an art studio in Madison, Indiana and goes back and forth from Payne Hollow. He stays up late, and sometimes, I need help keeping awake during these late-night shifts. Storms follow the river east, and Madison is upriver from here, so I’ll call Paul and warn him of storms or something, and we will end up talking for hours. He often tells the same story, but for a complete study of the American writer Harlan Hubbard, all is well with the tradition of river storytelling or yarn spinning as we like to call it.

I’ve spent many a dark hour in the pilot house just a thinkin’ and can see everything from the Captain’s seat. There are many metaphors here on the river; the river will make its own way, the river symbolizes the spirit, and the bridges, to name a few sources. The Railroad Bridge over the Falls of Ohio is what I gaze at for solitude. Mostly because I probably know the people driving the trains; I used to be one of them. After sixteen years of working on the railroad, I can speak to the poetic literal sense of place that the railroad has created. Getting a job here on this steamboat was a step backward in technology and innovation and a logical next step for me. The railroads bankrupted river transportation, and the railroad almost bankrupted me, and that is the rest of the story.

Yesterday, while on watch, I was reading Shanty Boat while texting with a rail hobo friend and had an epiphany. The revelation happened after talking with some homeless folks. Somewhere in the texting and the homeless folks, I picked up the book and read a passage about the people who lived on the river outside of Brent, KY, where Harlan and Anna Hubbard built their shanty boat.

The thoughts “of the river” and “on the fringe” kept coming to mind. Harlan wrote extensively about how he sincerely respected the “river people.” Back in his day, the 1920s—1940s, the people living along the river in shanty boat communities were looked down on as outcasts of society. Harlan deeply admired “those people,” and that was my revelation—more like many rivers arriving at a confluence. I am at a convergence of sorts; there is no midlife crisis.

Part of the epiphany was realizing that Harlan Hubbard was as old as I am now when he and his wife decided to leave the river life of a shanty boat and hand-build a house on the banks of the Ohio. Most of my closest friends are considered outcasts. Life On The Fringe Of Society is the subtitle of Harlan’s journal about living at Payne Hollow, and that is where I seem to have arrived during this fifty-year journey on the river of life. I have come to a revelation at the confluence.

A few months ago, I got a rare chance to read Harlan’s Payne Hollow Journals at Payne Hollow while sitting in the seat and at the very table where he wrote down his daily reflections. It was surreal, like the surreal thought about how weirdly connected I have become to some sort of river story. I better roll another smoke and go up to the pilot house. Things are getting too thick to navigate and too thin to plow. We will get to what that means shortly.

I am in the pilot house of a one-hundred-and-six-year-old steamboat. A railroad train horn sounded off a haunting blast in the distance. Well, it’s too thick to navigate and too thin to plow, meaning the river is too low, the silt is too thick to push through, or it’s foggy. When I ask them about it, I get several answers from different captains and engineers. The river saying comes from a song by John Hartford titled, Go On Let Him Mama. The lyrics to that song happen here almost daily. My interpretation of that John Hartford chorus is: that things are getting complicated and have many layers that some folks might need help understanding. Well, go on, let him momma —don’t put him down for that now and ...

As I was about to get up and make my way up to this isolated spot, a young man I had spoken to the other night approached with a damaged bike on his shoulder, a swollen eye, bleeding profusely, and looking somewhat shaken. He was trying to stay composed as he asked for a cigarette. I rolled him one and asked if he was okay. He told me he was stabbed in the eye with a screwdriver. I hand him the cigarette and reach out to give him a light. His hands cupped around the flame, and a few drops of warm blood and sweat dropped on my hand. This kid was dirty as fuck and had a puss-blistered rash, that he was picking at. just above his pants line. So much for social distancing.

While we talked, he constantly looked over his shoulder and couldn’t help but get welled up with rage as he told me his story. He was like this before, but not this bad. The anger was not directed at me, so I went inside, gathered some paper towels, and soaked them in hydrogen peroxide. The last time we talked, he told me about the homeless camp on the river, about a mile away, near Portland. I asked if there was anything else I could do for his wound, and he said he would get help down there. Many folks come through here on their way home to the camp; some stop, and others don’t, but I see them.

Of course I have to be careful, careful of many things. Like, yes, I washed my hands after giving that worn-out brother a light. I am keeping my physical distance as much as possible because of the national pandemic with the COVID-19 virus. I have to be careful how I talk about this work because I am a city employee, and this hotel front desk job, to a homeless crisis, is far above my pay grade. I am not a first responder and have no business acting like a small-town river doctor. Calling the Police or an ambulance is undoubtedly not an option; he wouldn’t have entertained the idea.

I also must be mindful of how I talk about my friend Paul and his relationship with Harlan Hubbard. I want to honor Harlan as a great Kentucky writer and Paul’s relationship with him. The more I talk with Paul, the more his story becomes too thin to plow or thick to navigate. The last time I visited Paul at his studio in Madison, he showed me a newspaper article from the local rag that read like a hit piece on his intentions at Payne Hollow. Even though the article was from a long time ago, I could tell it still profoundly hurt him.

Do y’all get this? I mean, really, come on ... this is a “sense of place” as fuck transcript. I am as Louisville as hell! Born of good German-Swiss-Catholic, Lebanese / Syrian east Jefferson Street, Schnitzelburg, heritage! Lately, my writing has been like a puffed-up bird looking for a mate. Hey, I am looking for an Anna. Get it? The simple life. Shit, Mile Marker 604 on the Ohio. I need to focus better and be careful what I say and write. I am seemingly desperate, and that is embarrassing.

A tow is shoving upriver past the boat now. I can see its headlight cast over the Belle and feel the bow wave surging as it passes. The Belle is slightly rocking now. The towboat captain turned his high-power spotlight on the pilot house, and I waved. I drank a sip of cold coffee and spilled a little on the floor. Engineers do that. You can tell if an engineers been working by looking for spilled coffee or grease prints on the wall.

I am now back in Mark Twain’s time —so it goes, I better go on watch on the Mary Miller. She has air conditioning, and would be a nice place to sit and cool off for a minute. The streets have been hot. Louisville’s been protesting the murder of Breonna Taylor for over 50 days and nights. I am worn the fuck out, and so is everybody else. Arrest the suspects already, would ya, boss? Mayor. What gives.

I am on the Mary Miller now. It’s nice and cool -dark, spooky. There is a constant drone coming from a pump down in the hold. I am getting exhausted. Tonight is going to be a long night. The second the Captain shows up in the morning, I will head back to the house as I have been up almost 24 hours. I used to do this kind of work on the railroad. Fatigued out the wazoo driving trains way more fatigued than now. I have no clue how I used to pull those midnight runs off.

It’s spooky on this boat but not on the Belle. If there are any ghosts here, they are on the Mary M. Miller. Another tow is pushing upstream as the boat gently rocks my soul. I am on a river. A river-man, now. Captain told me so.

The boat I am on now is haunted. Maybe not, but this Wharf is. Down here by the Mary is where the York and Lewis and Clark historical markers are. And actually, York is sitting with me now. After he got his freedom from being whitewashed into history, he became a Teamster, and I am a retired Teamster. York and I have lots to talk about. I am unsure what this writing is about or what I am trying to say tonight. I can say that things lately have been absolutely nuts. I committed to myself and intend to eat much better today. So, I went to the Health-food store, Rainbow Blossom and got some supplies. Goldenseal, dried and sugared ginger, four chocolate bars, good ramen, couscous, nuts and figs.

Back to the Belle. I left my tobacco pouch in the pilot house, so I walked up the grand staircase, took two flights to the top, and then back down to the Broaddus. My hip and knee can’t take much more of this. Every step I take adds another second to the time it takes to fall asleep. Sometimes, that can be as much as three hours. Just as many hours as I have left because half of my watch is over. 5 a.m. is close, and five looks better than oh three hundred hours. If I sit here much longer, I will start nodding off. My plan is to rope-a-dope this night like Muhammad Ali. Peace be upon him.